“Refugees” or “migrants”?

How words affect lives and rights

Refugees have rights, reflected in the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, limited to protect European refugees after two World Wars. The New York Protocol of 1967 made the Convention universal for all refugees, being mandatory for the signatory countries.

The greatest risks of irregular migration

Migrating in a safe and dignified way is a right of all human beings. However, doing it irregularly can have consequences that can mark people's lives.

“Refugees” or “migrants”?

How words affect lives and rights

People who move from one country to another deserve to have their dignity and human rights respected. There are various reasons why people must leave their homes; Therefore, the international obligations that arise and apply with respect to the lives that were, are or could be at risk in the event of returning to the place of origin vary.

Seeking refuge is a right

The right to asylum is regulated by International Law and is an obligation of States.

Migration and human rights

“People are dying while governments spend billions on border control”

International law specifically defines and protects refugees. These are people who seek protection in another country after having fled their homes to escape persecution, conflict, violence, serious violations of human rights or other events that seriously alter public order. Consequently, since their country of origin is unable or unwilling to protect them, these people need another country to provide them with international protection. In these cases, people exercise a fundamental and universal human right: the right to request and enjoy asylum. According to international refugee law, any person who meets the criteria of this definition is a refugee and should therefore receive such treatment (even if he or she is still awaiting recognition by States or UNHCR).

International law indicates that States have specific obligations towards refugees; between them:

- Guarantee them access to the territory and to request asylum.

- Do not penalize them for crossing international borders irregularly – that is, without authorization or the necessary documents – to seek protection, since requesting asylum is not illegal.

- Guarantee the protection, respect and exercise of their fundamental human rights.

- Guarantee that they are not expelled or returned (principle of non-refoulement) to situations where their life or freedom is in danger.

In some countries, refugees have access to other forms of legal stay, which include mechanisms for free movement, work permits and student visas; therefore, they may choose not to apply for asylum. However, these and other forms of residence do not affect the need for or right to receive international protection. Asylum seekers are those who express their willingness to request international protection, or who are waiting for their application to be resolved. In this regard, States have the obligation to guarantee that any person who approaches their borders requesting asylum has access to the territory and presents their case, which must be evaluated in a fair and efficient manner. While not all asylum seekers will have their refugee status recognised, claims must be assessed fairly and efficiently.

International law does not define who a migrant is; However, the term has been used to refer to people who choose to cross borders for reasons other than direct threats of persecution, serious harm or death; for example, job or educational opportunities, or family reunification. Other factors that come into play include famine, extreme poverty, and hardship caused by environmental disasters.

Typically, those who leave their countries of origin for these reasons do not need international protection, since, unlike refugees, they continue to enjoy the protection of their country upon returning to it or even while abroad.

Although they do not meet the criteria detailed in the definition of a refugee, it is likely that, at different times during their journey, migrants require help, assistance or protection of their human rights. In that case, they are protected by international human rights law and, in some circumstances, in defense of these, they may enjoy the right not to be deported or returned to their country of origin.

Mixed movements are increasingly common around the world, that is, those in which refugees and migrants travel the same routes by land or sea. Although their legal status and motivations differ, they may face the same dangers along the way, including violence, abuse and exploitation from human traffickers, smugglers, criminals, armed groups, corrupt agents, or even border guards and other officials. .

A migrant person will not automatically become a refugee due to experiences or incidents of this type (since refugee status depends on the person being unable to return to their country of origin due to the dangers, violence or harm they experience ran away). However, States must adopt a humane and rights-based approach to their borders. Specifically, they must ensure that people in need of international protection – that is, refugees – have access to asylum and that victims of trafficking or human rights violations, whether refugees or migrants, are quickly identified and supported.

from the codified body of laws developed last century specific to refugees (the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol as well as other legal texts, such as the 1969 OAU Refugee Convention), to the more recent New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants, and the two distinct frameworks it spurred - the Global Compact on Refugees and the Global Compact for Migration.

A problematic trend is becoming popular in the media, political and statistical narrative, which consists of using the word migrant as an umbrella term that encompasses refugees and migrants. Combining the two terms is not only imprecise, but can also have serious consequences for people in need of international protection.

Using the word migrant – or using qualifiers such as illegal, unauthorized or undocumented – to incorrectly refer to refugees and asylum seekers:

- It distorts the status of refugee, which is a specific legal figure.

- It hinders access to certain legal protections, including the right to cross borders to seek and enjoy asylum.

- It diminishes the responsibilities of States, since it downplays the obligations that they have to respect the right to request asylum without any distinction, including the modality of arrival.

- It threatens the lives or safety of refugees by not being identified in mixed movements and by not receiving the protection they need, which exposes them to other risks.

- It dismisses the experiences of refugees, as well as the risks and dangers they have faced due to wars, persecution and conflicts.

- It fuels anti-refugee and anti-asylum policies, which include denial of access to asylum and territory, returns by land or sea, violence and ill-treatment at borders, forced returns to dangerous contexts (refoulement), as well as attempts to evade or send people asylum seekers to other countries (outsourcing).

To ensure clarity and precision, as well as to avoid the consequences inherent in combining the terms refugee and migrant, using the phrase refugees and migrants is the correct way to recognize the specific and pressing needs of those who are part of mixed movements. The use of this phrase would facilitate adequate identification and response for the parties involved, as it would ensure that refugees have access to asylum and that vulnerable migrants receive the support they specifically require. In broad terms, the phrase refugees and migrants refers to individuals, people or people in situations of human mobility.

There is a lack of a Sustainable Development Goal focused on migration

The 2030 Agenda must address the movement of people as an issue that must be governed globally, and not as a problem that we have to limit. Halfway to the 2030 Agenda deadline, we are leaving more than half the world behind. Progress on more than half of key poverty, hunger and environmental goals is insufficient, and 30% have stagnated or regressed.

Now that we have reached the world of progress on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), it is necessary to address the migration gap of the 2030 Agenda, so that migration is governed globally and not managed as a problem that we must limit. A new migration discourse and framework must ensure the positive impact of migration, thus advancing the interconnected success of the 2030 Agenda and the transformation towards a new social contract.

The SDG framework recognizes migration as a driver of development. It states that “the objectives and goals will be met for all nations and peoples and segments of society” and also that the most vulnerable—women and migrant minors—are less protected. Still, this scope and discourse are limited and underrepresent the complex and multidimensional nature of migration.

Only goals 8.8 (Protect labor rights and promote a safe and secure work environment for all workers, including migrant workers), 10.7 (Facilitate migration and orderly migration policies) and 10.c (Reduction of remittance costs of migrants) explicitly mention migrants or migration. In 2020, indicator 10.7.4 was included, the only one that addresses refugees.

The need to recognize climate refugees in international law must be included in the 2030 Agenda and its objectives

The continued omission of migration from the SDGs will leave many behind tomorrow

Who is left behind?

The 2030 Agenda shows insufficient inclusion of migration. It potentially reflects the migration tensions of 2015. The Agenda must therefore stop framing migration as a temporary and unplanned circumstance that needs Western management and must be embraced as an integral driver of sustainable development and transformation that must be governed at the national level world.

In the context of climate change, migration governance is especially important. Today, more than a billion people live in low-lying areas that are at risk of the effects of coastal climate by 2050, according to the World Bank. The extent to which climate change will magnify demographic movements in the near future depends on global cooperation and coherent mitigation and adaptation policies within different multilateral frameworks.

In 2019, 25.9 million refugees were excluded and left behind in the SDGs. This is due to their exclusion in SDG data collection, reporting, monitoring and development plans, and the fact that climate refugees are not yet recognized under international law.

The lack of data on refugee well-being is serious. 70% of Syrians in Lebanon live below the national poverty line, compared to 26% of those born and residing in that country. In the case of Ethiopia, 6% of Eritrean children are reading fluently at age 10, while those born in Ethiopia reach 15%, according to data from the International Rescue Committee.

A new migration target could play a decisive role in several dimensions of sustainable development, ensuring that no one is left behind, addressing global challenges and being an engine of development. It would also serve to ensure that the specific needs and vulnerabilities of all types of migrants are explicitly addressed in national and global development agendas. The need to recognize climate refugees in international law must be included in the Agenda and its objectives, thus committing to human rights, equal opportunities and social inclusion, regardless of immigration status.

Building on the Global Compact on Migration (GMP) would serve as a solid and fundamental framework to improve commitment and accountability, policy coherence, data disaggregation and collection, cooperation and a paradigm shift in the notion of migration as a problem to be managed.

The Global Compact on Migration and the SDGs already share several concepts of decent work, cooperation, legal status, vulnerabilities and access to basic services. However, in promoting the pact as an objective, a global consensus on social protection, reintegration, remittances, contributions, discrimination, human trafficking, pathway development, documentation and identity must be more explicitly established. Greater responsibility is needed around global collaboration and migration commitments. Only 163 countries have signed the PMM, while all 191 members of the United Nations are committed to the SDGs. This means that key countries such as the United States, Italy, Israel, Latvia, Poland and Australia will be held accountable for their global migration commitments.

The continued omission of migration from the SDGs will leave many behind tomorrow. The need to go beyond the limited linear notion of classifying countries as origin, destination or transit and their corresponding responsibilities must be translated into global commitment and migration governance. A goal that recognizes and implements this change will paint a more realistic migration picture, in which migration is a complex driver of development rather than a challenge. We are faced with a unique opportunity to commit to defining a realistic path in which no one is truly left behind.

Beyond its institutional relevance, a new SDG will contribute to the migration debate and go beyond the idea of migration as a threat to society or a humanitarian challenge. This message is not only directed at conservatives and their idea of migration as a cultural and economic burden, but also at civil society, NGOs and political parties. The immigration discourse must be reconfigured for this idea to be carried out, and this article aims to challenge the victimizing and savior views towards immigrants, even from NGOs and the political left. Looking to the future, a migration SDG would be responsible for reconfiguring the migration discourse and its vertical frameworks, generating inclusive dialogues that actively integrate and listen to people.

Explore the interrelationships between each SDG and migration

Hover over a Sustainable Development Goal window for more information

Migration can be an effective poverty reduction tool among migrants and families, and can make important contributions to development activities in both countries of origin and destination.

Food insecurity can be a factor that drives the migration of individuals and families.

Addressing migrant health and well-being issues is a precondition for social and economic development.

Education can facilitate the socioeconomic integration of the children of migrants, and improve their means when they reach adulthood.

Migration can be a source of empowerment for women and girls, but it can also make them vulnerable to violence, abuse and sexual exploitation.

Water scarcity and water-related issues can affect living standards, food security and health, which in turn can be a driver of migration.

Alternative, inexpensive solutions can benefit vulnerable or displaced communities with little or no access to electricity.

Decent work and adequate working conditions for migrants are essential elements in ensuring that they become productive members of society and contribute to economic growth.

Migrants can be carriers of valuable skills and knowledge for their countries of origin and destination, and contribute to technological development, research and innovation.

Effective migration governance is vital to achieving safer, orderly and regular migration.

Migrants contribute to the dynamism of cities and make them vibrant and dynamic centers of economy and life.

Promoting sustainable consumption and production patterns can help protect migrant workers from exploitation.

Migration can be a potential adaptation strategy to climate change and a means to foster resilience

Combating the degradation of marine and coastal ecosystems and diversifying the livelihoods of communities that depend on marine resources can help address forced displacement and migration

Deforestation, land degradation, desertification and biodiversity loss can have profound impacts on communities whose livelihoods depend on natural resources, and can be drivers of migration

Stronger, more transparent and accountable institutions and better access to justice can help protect and promote the rights of migrants

Timely, reliable and comparable migration data can help policymakers establish evidence-based policies and plans to address migration-related aspects of the SDGs.

The dangerous and dark migration industry of Darien

Every year, thousands of people of different nationalities, including Venezuelans, Haitians, Cubans and Africans, among other countries, undertake the dangerous journey through the Darien. The reasons are diverse, but most seek to escape violence, poverty and lack of opportunities in their countries of origin.

Seeking refuge is not a crime

A refugee is a person who is outside their country or region of origin due to well-founded fears of persecution for reasons of ethnicity, religion, nationality, membership of a social group or political opinions; or due to force majeure such as catastrophes, wars or natural disasters, and who cannot or does not want to claim the protection of their country to be able to return.

Most of the world's population has had the experience of leaving the place where they grew up. Maybe they just move to the nearest town or city. But some people will even have to leave their country, sometimes for a short time, but sometimes forever. Elery day, all over the world, there are people who must make the most difficult decision of their lives: leaving their home in search of a better, safer life.

There are many reasons why people try to rebuild their lives in another country. Some people leave home to find work or study. Others are forced to flee persecution or human rights violations such as torture. Millions are fleeing armed conflicts or other crises or violence. Some no longer feel safe and may be persecuted simply for being who they are or what they do or what they believe; for example, due to their ethnicity, religion, sexuality or political opinions.

These journeys, all of which begin with hope for a better future, can also be fraught with danger and fear. Some people are at risk of being victims of trafficking and other forms of exploitation. Some are detained by the authorities as soon as they arrive in another country. When they are adapting and beginning to build a new life, many suffer racism, xenophobia and discrimination on a daily basis. Some people end up feeling alone and isolated, having lost the support networks—communities, colleagues, families, and friendships—that most of us take for granted.

WHY DO PEOPLE LEAVE THEIR COUNTRY?

There are many reasons why it might be too difficult or dangerous to stay in your own country. For example, boys and girls, women and men are fleeing violence, war, hunger and extreme poverty, due to their sexual or gender orientation or the consequences of climate change or other natural disasters. It is often due to a combination of these difficulties.

Those who leave their country are not always fleeing danger. They may believe that they have a better chance of finding work in another country because they have the training or capital necessary to look for opportunities abroad. Or they may want to join family or friends who already live in another country. Or perhaps they are trying to start or finish their studies. There are many reasons why people embark on a journey to build a life in a new country.

A refugee is someone who has had to flee their own country because they are at risk of serious human rights violations and persecution there. The risks to his safety and her life were so great that she felt she had no choice but to leave and seek safety outside her country because her own country's government was unable or unwilling to protect her from those dangers. Refugees have the right to receive international protection.

An asylum seeker is someone who has left their country and seeks protection from persecution and serious human rights violations in another, but who has not yet been legally recognized as a refugee, as they are waiting for a decision to be made. about your asylum application. Requesting asylum is a human right. This means that anyone must be allowed to enter another country to apply for asylum.

There is no internationally accepted legal definition of a migrant person. Some migrants leave their country because they want to work, study or reunite with their family, for example. Others believe they must leave because of poverty, political instability, gang violence, natural disasters, or other serious circumstances there. Many people do not fit the legal definition of a refugee, but could be in danger if they returned to their country.

It is important to understand that, although migrants are not fleeing persecution, they continue to have the right to protection and respect for all their human rights, regardless of their status in the country to which they have moved. Governments must protect all migrants from racist and xenophobic violence, exploitation and forced labor. Migrants should never be detained or forced to return to their country without a legitimate reason.

The problem is not the people, but the causes that push families and individuals to cross borders and the short-sighted and unrealistic ways in which politicians respond to them. Governments must ensure that refugees, asylum seekers and migrants are safe and are not tortured, discriminated against or left in poverty.

The person behind the label

Each human being has more than one identity. “Refugee”, “migrant” and “asylum seeker” are only temporary terms that do not reflect the entire identity of the women, boys, girls and men who have left their home behind to start a new life in a new country. When we use these labels we must remember that, of the many ways in which each person describes themselves, these terms refer to only one experience: that of leaving their country. But these people's identities are made up of many more things.

Most of those looking to live abroad feel that the experience of leaving their own country does not fully capture who they are. Like all people, they are complex and unique human beings, and they may choose to identify themselves as coming from a certain country or region, belonging to a group that speaks a certain language or shares a culture. Or they could say they are a teacher, a doctor, an artist, a passionate soccer fan, a father, a sister, a son or a mother. The legal status of a person cannot fully express the identity and personality of a refugee, asylum seeker or migrant. You cannot know anyone only through their legal status.

While the general public uses both terms interchangeably, there are fundamental differences between "refugee" and "migrant"

Refugees are people who are outside their country of origin for fear of persecution, conflict, generalized violence, or other circumstances that have seriously disrupted public order and, consequently, require international protection. The definition of a refugee can be found in the 1951 Convention and regional refugee instruments, as well as in the UNHCR Statute.

Migrant

Although there is no legally agreed definition, the United Nations defines a migrant as "someone who has resided in a foreign country for more than one year regardless of the causes of his or her transfer, voluntary or involuntary, or the means used, legal or others". Now, common usage includes certain types of shorter-term migrants, such as seasonal agricultural workers who move for short periods to work planting or harvesting agricultural products.Laws for migrants, refugees and asylum seekers

Regardless of how and why they arrive in a country, international law protects the rights of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers, who have the same rights as other people, plus special or specific protections, such as the following:

the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (article 14), which states that, in case of persecution, everyone has the right to seek and enjoy asylum in any country;

the 1951 UN Refugee Convention (and its 1967 Protocol), which protects refugees from being returned to countries where they risk persecution;

the 1990 Convention on the Rights of Migrant Workers, which protects migrants and their families; regional legal instruments on refugees (such as the 1969 OAU Convention, the 1984 Cartagena Declaration, the Common European Asylum System and theDublin Regulation).

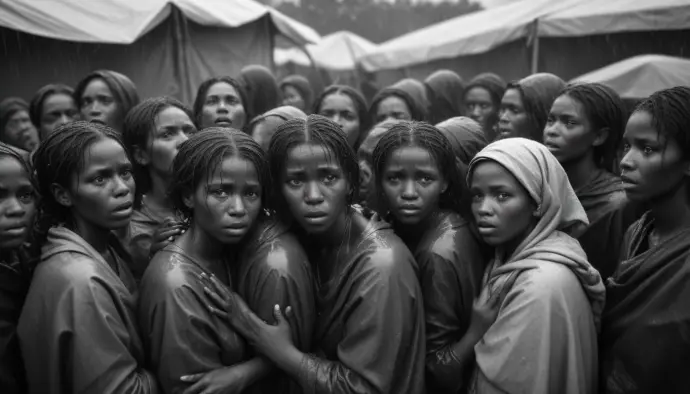

Everyone desires safety, dignity & freedom. Yet racism, xenophobia & discrimination are thriving — causing untold suffering & denying humans these basic needs.

- No Human Being is Illegal. End the criminalisation of migration.

- Hope has no passport: Open regular migration pathways.

- From every corner, we dream the same. Stop xenophobia.

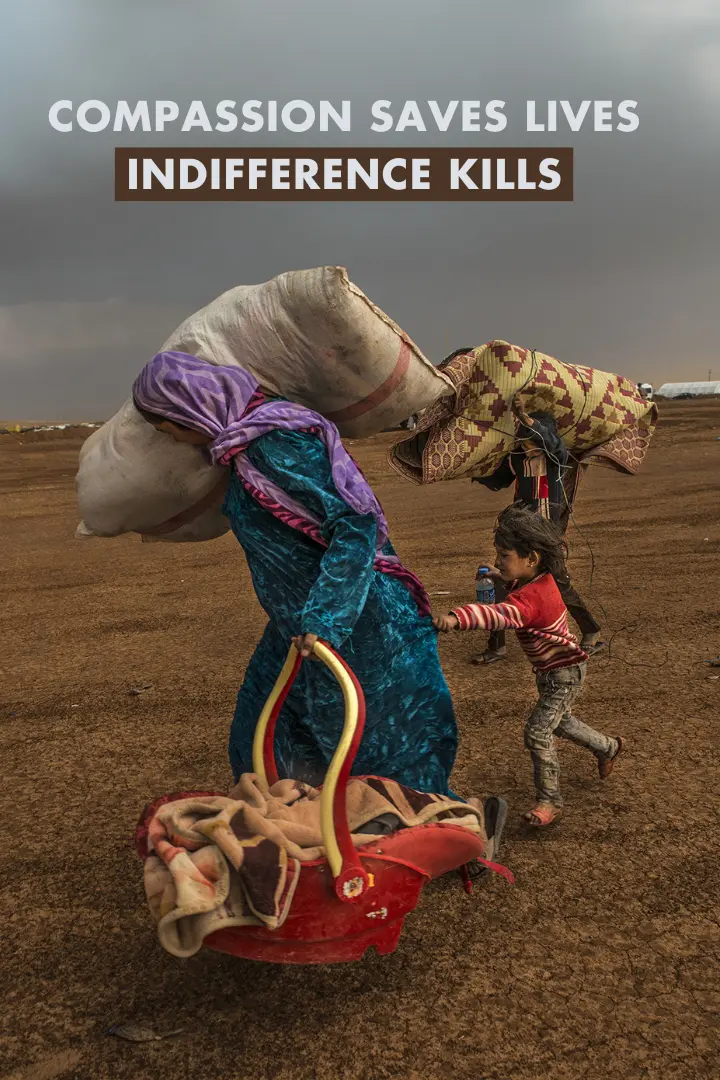

- Compassion saves lives, Indifference kills.

AI and the Future of Asylum: Risk Assessment and Refugee Protection

Technology to the Rescue: Innovations to Improve the Lives of Refugees

Shelter in the Net: How the Internet is Transforming Refugee Aid

The 1951 Convention: Understanding the Legal Framework for Refugee Protection

The Right Not to Be Returned: Principle of Non-Refoulement in Refugee Protection

The Challenge of Resettlement: Policies and Practices for a New Life

The Challenge of Political Asylum in the Human Rights Framework

AI at the Border: Facial Recognition Technology and Immigrant Rights

Uncertain Fate: The Asylum Search and Its Bureaucratic Complications

The Digital Footprint: Data Use and Privacy in Refugee Management

Refugees and Technology: Facilitating Digital Access for Integration and Support

Refugees and displaced women:The specific challenges of women in humanitarian crises

Women in the Spotlight: Gender-Based Violence in Refugee Camps

Migrant women: Facing unique challenges in search of a better life

Human Rights and Migration: Facing the Crisis with Humanity and Justice

Eco-Refugees: The New Face of Climate-Forced Migration

Crossing the Desert: Dangerous Routes and the Reality of African Refugees

The Mediterranean Crossing: Stories of Despair and Hope

Climate Change and Forced Migration: A New Kind of Refugee

Climate Displaced: Environmental Refugees' Struggle for Survival

Climate Migration: Unraveling the Causes and Consequences for Displaced Communities

Displaced by Mining: The Silent Crisis of Environmental Refugees

Refugee Urbanization: Challenges and Human Rights

Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons: The Invisible Aftermath of Armed Conflict

IHRO NEWS

IHRO NEWS