Why Facebook and Instagram have become platforms for child sex trafficking

The Guardian newspaper has been investigating the grooming and sexual exploitation of minors on social media for more than two years. It reveals the inability of the tech giant Meta to prevent criminals from using its platforms to traffic children for sexual purposes

- The surviving victims

- The court documents and the prosecutors

- The responsibility to report

- The moderators

- The limits of the law

- The consequences

Content warning: The following story contains descriptions of sexual abuse, exploitation and trafficking of minors.

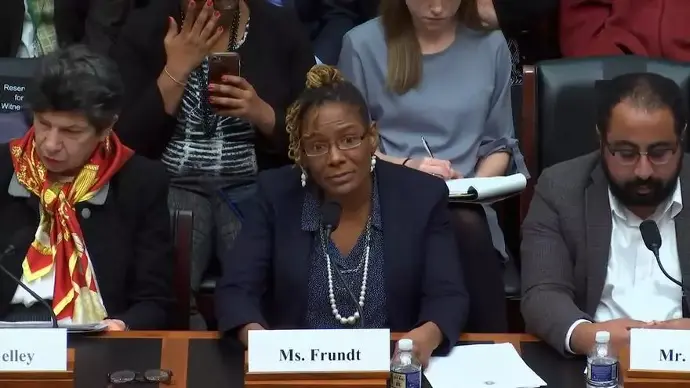

Maya Jones* was just 13 when she first walked through the doors of Courtney's House, a shelter for sex trafficking victims ages 12 to 21 in Washington, DC. “Despite her youth, Maya was very broken by what she had been through,” said Tina Frundt, founder of Courtney's House. Frundt, one of the nation's leading experts on combating child sex trafficking, has worked with hundreds of young people who have been victims of horrific forms of sexual exploitation by adults. Despite her extensive experience, when Maya opened up about what she had experienced, Frundt was shaken.

Maya told her that when she was 12, she started receiving messages on her Instagram account from a stranger. She said the 28-year-old man had told her she was very pretty. Maya also told her that after she started chatting with the man, he asked her to send him nude photos. The man told her he would pay her $40 for each of the images. He seemed friendly and kept complimenting her, which made her feel special. Maya decided she wanted to meet him in person. The man then made the following request: “Can you help me make money?” The man asked Maya to pose nude for some photos and to give him her Instagram password so he could upload the photos to her profile. Frundt says Maya told her the man, who now called himself a pimp, was using her Instagram profile to advertise her for sexual purposes. Soon, men who wanted to pay to have sex with her began sending messages directly to her account, asking for a date. Maya told Frundt that she watched, terrified, what was happening on her account, as the pimp negotiated the prices and logistics of the meetings at motels in the capital. She didn't know how to say no to this adult who had been so kind to her. Maya told Frundt that she hated having sex with these strangers, but she wanted her pimp to be happy.

One morning, three months after meeting the man, a passerby found Maya slumped on a street in southeast Washington, half-naked and confused. The night before, Maya told him, a client had taken her to a location against her will, and she later recalled that she had been gang-raped there for hours before being left lying on the street. “She was traumatized and blamed herself for what happened. I had to work hard with her to get her to realize it wasn’t her fault,” Frundt explained when we visited Courtney’s House last summer.

Frundt, who has helped more than 500 minors since founding Courtney’s House in 2008, says the first thing she does now when a child who has been trafficked as a child comes to the shelter is ask for their Instagram account. It’s not the only platform predators use to sexually exploit minors who pass through the shelter. The expert points out that although it is not the only one, Instagram is the most frequent.

In the 20 years since the appearance of social networks, child sexual exploitation has become one of the greatest challenges facing technology companies. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), human traffickers use the Internet as a “digital hunting ground”, allowing them to contact both clients and potential victims. Traffickers use social media platforms to recruit minors. The main social network, Facebook, is owned by Meta, the California-based technology giant whose platforms, which also include Instagram and WhatsApp, are used by more than 3 billion people around the world.

In 2020, according to a report by the Human Trafficking Institute (HTI), a US-based non-profit, Facebook was the most commonly used platform by sex traffickers to recruit and seduce minors (65%), based on an analysis of 105 child sex trafficking cases. The HTI analysis ranked Instagram in second place and Snapchat in third.

Grooming and child sex trafficking are separate acts but are often investigated and analyzed together. “Grooming” refers to the period of manipulation of a victim prior to sexual or other exploitation. “Child sex trafficking” is the sexual exploitation of a child specifically as part of a commercial transaction.

When the pimp flattered Maya and conversed with her, he was paving the way for his scheme; when he sold her to other adults for sex, he was trafficking.

Although people often associate “trafficking” with the movement of victims, either internally or from one country to another, under international law the term refers to the use of force, fraud or coercion to obtain labor, or in the purchase and sale of non-consensual sexual acts, whether or not there is movement involved. Since under international law minors cannot legally consent to any kind of sexual act, anyone who profits from or pays for sex with a minor — including profiting from or paying for photographs depicting sexual exploitation — is considered a human trafficker.

Meta has many measures in place to try to prevent sex trafficking on its platforms. “It is a priority for me to make everything we build safe and beneficial for children,” Meta founder Mark Zuckerberg wrote in a memo to staff in 2021.

In a statement in response to a detailed list of allegations against the company in this story, a Meta spokesperson said: “The exploitation of minors is a horrendous crime. We do not condone it and we work vigorously to combat it on and off our platforms. We actively work with law enforcement to apprehend and prosecute offenders who commit these heinous crimes. “When we become aware that a victim is in danger and we have information that could help save a life, we immediately make an emergency request,” the statement quoted the head of the intelligence centre at Stop the Traffic, a London-based non-profit that works with big tech companies to combat human trafficking. The head of the intelligence centre, who previously served as deputy director of the UK’s Serious Organised Crime Agency, said that “millions of people are safer and traffickers increasingly frustrated” thanks to the organisation’s collaboration with Meta.

Despite this claim, the Guardian has had access to victim accounts, interviews, US court documents and information on trafficking complaints over the past two years. It has repeatedly heard claims that Facebook and Instagram have become major platforms for child trafficking. More than 70 sources, including victims and their families, prosecutors, child protection experts and US content moderators, have been interviewed to understand how trafficking groups use Facebook and why Meta is not legally responsible for trafficking taking place on its platforms.

While Meta claims it is doing everything it can, the Guardian has had access to evidence that it is not reporting the threat and is not even aware of the scale of it. Many of those interviewed said they felt helpless and had failed to get the tech giant to act.

Names marked with an asterisk * have been modified to preserve anonymity.

May 27, 2023

IHRO NEWS

IHRO NEWS